New Report Explores Role of Race and Socioeconomics in Achievement Gaps

A Fordham report examines achievement gaps and socioeconomics.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Among other things, the study looked at which SES factors best explain existing achievement gaps, along with disparities among high-achieving students. The authors analyzed two sets of data from the federal Early Child Longitudinal Study, from 1998-99 and 2010-11.

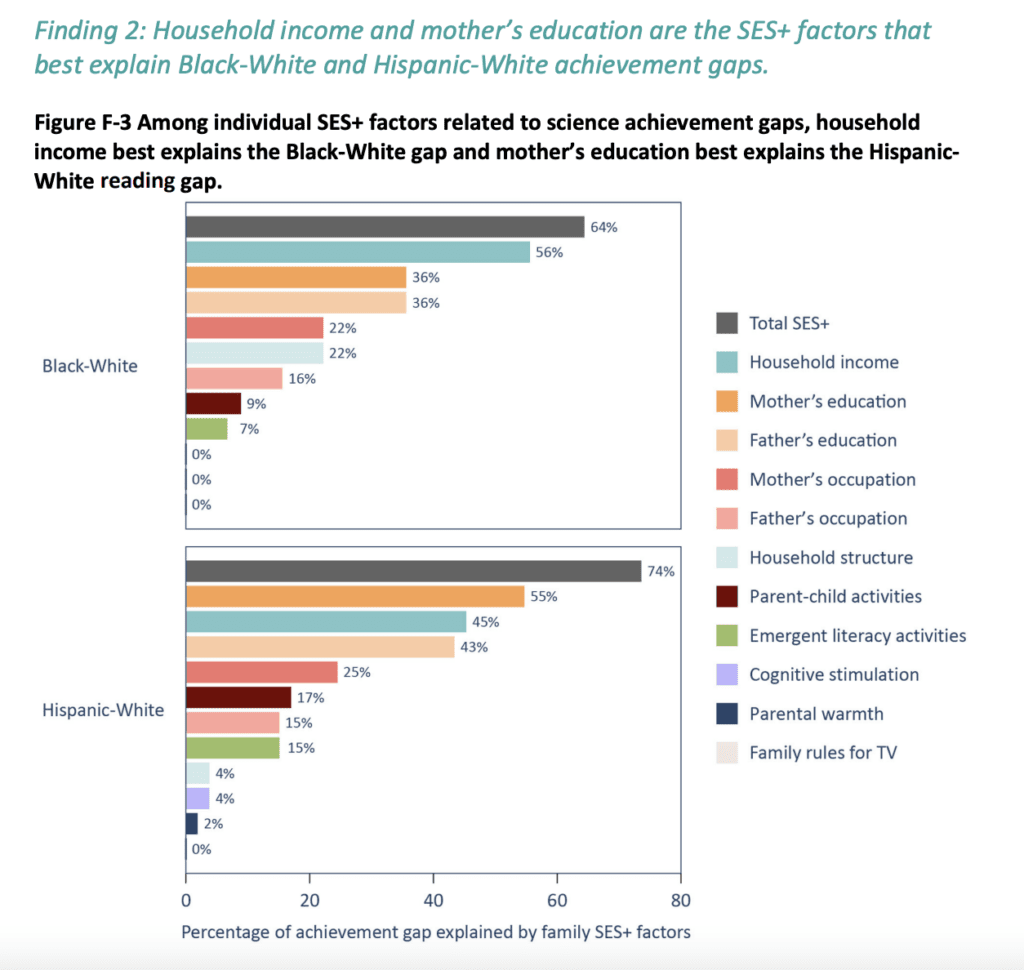

The study’s resulting analysis shows that “a broad set of family SES factors explains a substantial portion of racial achievement gaps: between 34 and 64 percent of the Black-white gap and between 51 and 77 percent of the Hispanic-white gap, depending on the subject and grade level.”

“Racial achievement gaps in schools are well documented and remain a significant cause of concern in education. Troubling too is that the role of socioeconomic disparities in mediating these gaps remains unresolved,” the institute’s website says. “While SES accounts for much of the racial achievement disparities, closing these gaps requires a comprehensive approach, including improving school quality and supporting family stability.”

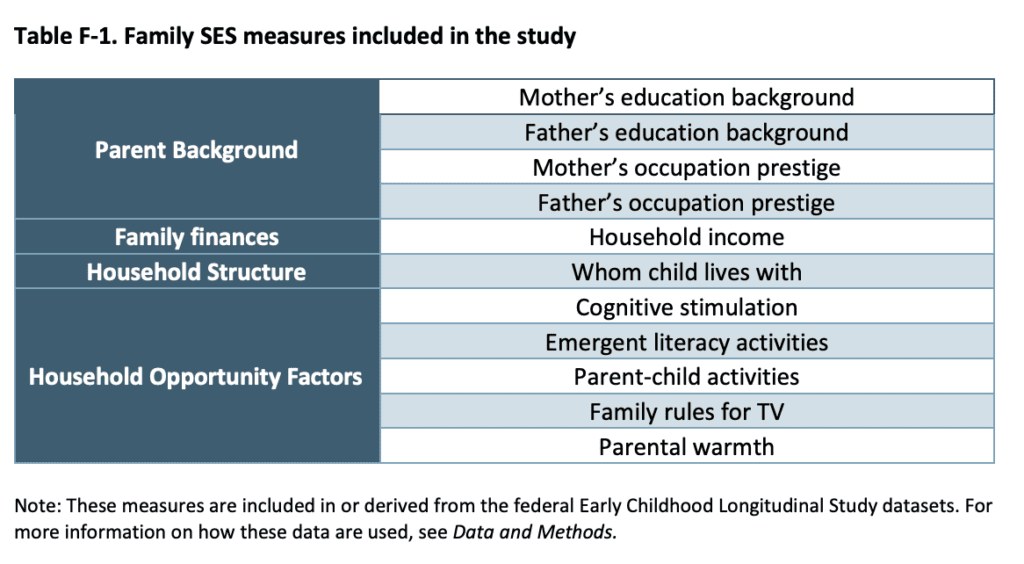

The institute’s study used a broad set of measures of family background, including parents’ education, family finances, household structure, and “household opportunity factors.” The latter measure refers to academic, enrichment, and familial activities.

The authors of the study, University of Albany’s Eric Hengyu Hu and Paul L. Morgan, identified the following key findings from their analysis:

- Racial achievement gaps decrease significantly when controlling for the SES factors (though SES explains more of the Hispanic-white gap than the Black-white gap).

- Of all the SES factors analyzed, household income best explains the Black-white gap in academic achievement and mother’s education best explains the Hispanic-white gap.

- SES indicators, and the extent to which they explain racial/ethnic achievement gaps, are stable over time (1998-99 and 2010-11).

- SES also helps explain racial and ethnic excellence gaps (differences in the proportions of student groups within the highest achievement levels). The SES factors explain a larger share of Hispanic-white excellence gaps than Black-white excellence gaps across the board.

- The Black-white achievement gap grows as students age through elementary school, while the Hispanic-white gap shrinks.

Key findings from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute’s study.

To close such gaps, the authors recommend investments in early childhood education and income supplements, such as expanding child tax credits.

“Because achievement gaps are already evident by elementary school, including as early as kindergarten, investing in high-quality early childhood education programs, especially in underprivileged communities, may be beneficial in mitigating the effects of socioeconomic disparities,” the report says.

In addition to early childhood investments, the authors also propose the following solutions:

- Support programs to help parents earn their high school diplomas or higher education credentials.

- Economic support and financial aid for low-income families.

- Addressing racial and ethnic disparities, including the adoption of “curricula that reflect diverse cultures and programs that specifically support underrepresented students,” and student-teacher racial and ethnic matching.

“Whatever the approach, there is no denying the urgency of making the U.S. educational system more equitable,” the report says. “…The time to act is now. By enacting comprehensive and inclusive policies, we can narrow achievement gaps and create a more just educational landscape for the next generation.”

You can download and read the full study on the institute’s website.

A look a gaps in North Carolina

Achievement gaps — also known as opportunity or equity gaps — follow national trends in North Carolina.

In 2021-22, following the start of the pandemic, only 51% of students tested as grade-level proficient. Proficiency was even lower among historically disadvantaged students, at 33% for Black students, 40% for Hispanic students, and 35% for economically disadvantaged students.

While those rates slightly increased during the 2022-23 school year, gaps and low proficiency rates persist.

More highlights from the report

Thomas B. Fordham Institute President Michael J. Petrilli wrote in the report’s foreword that “the vast racial disparities in socioeconomic conditions and prenatal and early-life health experiences explain the achievement gaps we see between racial and ethnic groups, at least at school entry.”

Citing a 2004 paper by economists Roland Fryer and Steven Levitt, “Understanding the Black-White Test Score Gap in the First Two Years of School,” Petrilli writes that this suggests that “universal, race-neutral interventions designed to improve the academic, social, economic, and health conditions of the poor would lift all boats and would also narrow racial gaps.”

Using data from the federal Early Child Longitudinal Study — data cited by Fryer and Levitt, along with more recent data — Petrilli said the report aimed to answer a few questions:

- Had the relationship between socioeconomic achievement gaps and racial/ethnic achievement gaps shifted?

- Was the Black-white gap still growing during elementary school?

- And how did all of this look for the white-Hispanic gap and for subjects beyond just reading and math?

Here is a look at the measures explored in the institute’s paper.

The institute’s study found that family socioeconomic factors explain more “of the Black-white achievement gap in first grade reading than in other subjects and grade levels.” The report proposes this may be the case because parents play a larger role in teaching language skills to young children than they do for math and science.

“The advantages of high SES—and disadvantages of low SES—thus show up more for students’ initial reading skills than for their math and science ones,” the report says. “As students get older and benefit from classroom instruction, their relative advantages and disadvantages start to matter less.”

However, while the gap narrows with age, there is still a gap. According to the report, this likely means “we still haven’t closed the ‘school quality gap’ between Black students and their white peers.”

As mentioned above, the report also found that family socioeconomic factors “explain more of the Hispanic-white achievement gap than the Black-white achievement gap.”

According to the report, this could be because Hispanic children in Spanish-speaking families “have latent potential that is obscured by their lack of English skills.”

The report also suggests that non-socioeconomic factors, racism, and bias affect Black children at higher rates than their Hispanic peers.

“For lower-income Black children, who are more likely to experience deep, persistent poverty than other groups, the combination of ‘adverse childhood experiences’ might exacerbate inequalities,” the report says. “And for middle class Black children, bias, stereotype threat, and related factors might be especially at play. This might also be why the Black-white achievement gap grows over the course of elementary school, while the Hispanic-white gap shrinks.”

Petrilli concludes: “When it comes to the interplay between race, poverty, and schooling, the honest read is that it’s complicated. What’s undeniable, though, is that much hard work remains, especially when it comes to providing effective schools to marginalized students, especially those who are Black. Let’s keep at it.”

This article first appeared on EducationNC and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)