Study Shows Boosting Funds to Poor School Districts Lifts Student Achievement but Fails to Narrow Racial & Socioeconomic Achievement Gaps

This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new research and data. Go Deeper: See our full series.

More funding to low-income school districts lifts student achievement over time, according to an article published earlier this year in the American Economic Journal. Its authors find that districts provided with increased revenues by school finance reforms see improvements in standardized test scores, though the extra money hasn’t helped close persistent gaps between various racial and socioeconomic groups.

First circulated as a working paper in 2016, the article is part of a new and somewhat contentious literature on education finance that points toward a distinct thesis: When it comes to promoting learning, money — and the enhanced resources it brings — truly matters.

In the 1990s and 2000s, respected economists made the case that spending more on schools was an ineffective method of improving outcomes for disadvantaged and minority students. This study, conducted by Jesse Rothstein and Julien LaFortune of the University of California, Berkeley, and Diane Schanzenbach of Northwestern, argues the opposite. In an interview with The 74, Rothstein said that access to new data over the past few decades has allowed researchers to more precisely observe the effect of funding on school performance.

“Until relatively recently, we really didn’t have much data either way,” he said. Skeptics had drawn “strong conclusions” from the lack of clear links between money and achievement, he added, “but the new data has made it possible to generate evidence — and evidence beats no evidence.”

Examining 64 school finance reforms (SFRs) in 26 states between 1990 and 2012, the study finds that state-led action to combat funding disparities between school districts results in sharp increases in per-pupil revenues. These infusions of money are, in turn, associated with noticeable improvements to students’ math and reading scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Those effects are roughly twice the size, per dollar, as those of Tennessee’s Project STAR, a successful, federally funded class-size-reduction experiment that is often used as a comparison for education initiatives.

The trio of researchers confronted significant difficulties in interpreting results. Connecting NAEP scores to other databases, such as the school census conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics, required a painstaking process of sifting that Rothstein likened to samizdat.

“It was a huge challenge,” he said. “It turned out that there was a key [data table] that we needed that the Institute of Education Sciences had lost. But we found somebody who was able to locate a 15-year-old email thread in his inbox, and that had it as an attachment, which he forwarded to us. So it’s fair to say the NAEP data are difficult to use, not just for school finance, but for program evaluations more generally.”

Once Rothstein and his colleagues assembled the puzzle pieces, a clear picture emerged. The dozens of reforms, adopted by state legislatures in all regions of the country, constitute “arguably the most substantial national policy effort aimed at promoting equality of educational opportunity since the turn away from school desegregation in the 1980s,” they write.

Beginning in 1990 with the passage of the Kentucky Education Reform Act, state authorities began passing measures to reduce the huge gaps in local education funding between rich and poor districts. In most instances, the new laws were passed in response to court orders pressing lawmakers to meet requirements in their state constitutions to provide every student an “adequate” education. The authors refer to the three decades that followed, when billions of dollars were redirected to low-income districts, as the “adequacy era” of school finance.

Low-income districts received about $1,200 extra per pupil, per year (or about $700 relative to more affluent areas, since the reforms also sent more money their way). Crucially, the new state funding didn’t “crowd out” local education dollars raised by property taxes, which were kept at the same level. Recipients spent their windfall on instruction, by hiring more teachers and reducing class size, but also on capital improvements like building renovations, which were often sorely needed after decades of neglect.

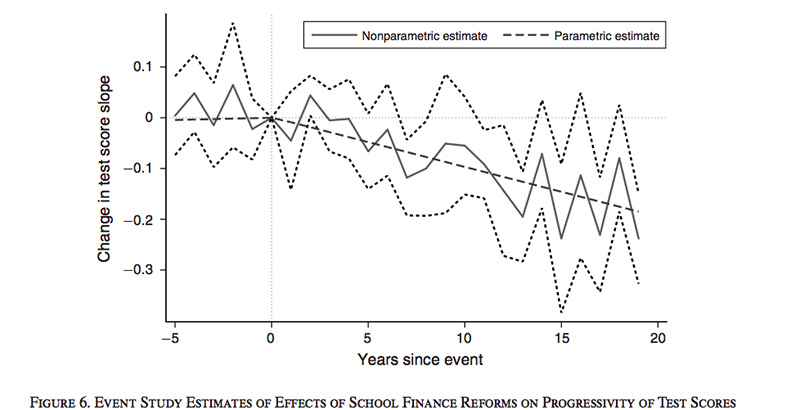

The impact on test scores was unambiguous: A decade after the SFRs were put in place, student achievement on NAEP in the targeted districts improved meaningfully. “Courts and legislatures can evidently force improvements in school quality for students in low-income districts,” the authors write.

Not everyone is convinced of the study’s findings, however. Eric Hanushek, an education economist and fellow at the conservative Hoover Institution, is one of the most influential researchers on the subject of school funding and perhaps the figure most prominently associated with the argument that school performance is largely unrelated to funding levels. He said that the study — along with other new research purporting to show the efficacy of greater education spending — didn’t pay enough attention to other education reforms taking place in states at the same time.

Court-ordered finance reforms “aren’t really surprises,” Hanushek told The 74. “Most of them have been going on for five or 10 years before the court finally rules. And states, legislatures, are doing a variety of things that they hope can improve the performance of their kids.”

“The difficult analytical issue is how you separate out spending from all kinds of other things, like changing the requirements for teacher certification, or changing the accountability rules, or the variety of things that state legislatures do over time.”

Beneath the study’s headline finding, there’s an additional wrinkle: While poorer districts mobilized the extra cash and saw higher scores, the study doesn’t detect a meaningful narrowing of achievement gaps between white and nonwhite, or poor and non-poor, students. The authors say that’s because some low-income school districts are nevertheless home to many high- or middle-income students, and vice versa. So even while low-income districts raised their NAEP performance in comparison to high-income districts, low- and high-income students within those districts were subject to the same inequalities as ever.

“That’s the explanation for why we don’t find significant closure of, say, the overall black-white gap at the state level,” said Rothstein. “There’s a lot of variation within districts, and the amount of between-district redistribution you need to make a dent in the overall gap would be enormous.”

That explanation doesn’t satisfy Hanushek. If extra funding improves the performance of low-income districts relative to higher-income ones, why wouldn’t it do the same for low-income students?

“They say [additional funding] closes gaps between districts, but not between kids — which is an odd finding, given that there is, in fact, a fair amount of segregation by both race and income across districts,” he said. “That doesn’t quite make any sense, does it? It says that you give districts money and the low-income districts do good things with it. But they’re not good things that help low-income kids.”

In response, Rothstein said that the study’s findings “are entirely consistent with the hypothesis (which I think should be the default absent evidence to the contrary) that the extra money in low-income districts helps low- and high-income kids in those districts equally.”

The study may hold increased relevance in light of this year’s release of America’s 2017 NAEP scores, commonly referred to as the Nation’s Report Card. After a period of widespread achievement growth in the late 1990s and early 2000s, most of the country has seen little or no growth on fourth- and eighth-grade math or reading since just before the Great Recession, when many states dramatically cut spending on K-12 schools. Per-pupil funding has still yet to return to 2008 levels in several states.

To compensate, public schools and their advocates have continued to press state governments for more money — through both legal action and street activism. In both Pennsylvania and Kansas, lawsuits to augment and redistribute education dollars are currently under consideration before state courts. And in a series of mass walkouts that have drawn national attention, teachers in West Virginia, Oklahoma, Kentucky, and Arizona have forced reluctant legislators to the table to pass funding increases.

Rothstein says the evidence makes a clear, if nuanced, case for money as a tool to improve school performance. But he also acknowledges that there are limits to the strategy, adding that additional reforms are necessary to offer an equal education to poor kids.

“This isn’t something you can just keep doing more and more and more of,” he said. “At some point you’ve probably gotten to a place where funding redistribution is not the primary lever — even if you think it works. These reforms are kind of a binary thing where, once you’ve done them, you’ve done them.”

Go Deeper: This is the latest article in The 74’s ongoing ‘Big Picture’ series, bringing American education into sharper focus through new numbers, research, and reporting. Get the latest stats, charts, and analysis delivered straight your inbox by signing up for The 74 Newsletter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)