Researchers Combed Through Over 1,600 Teachers of the Year Since 1988. Here’s What They Learned about the Winners

Get essential education news and commentary delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter.

The National Teacher of the Year program is a unique fixture in America’s education landscape — an annual, highly publicized recognition of excellence in the art of teaching, complete with a national tour and a trip to the Rose Garden. One day you’re leading a tenth-grade biology seminar; the next, you’re a combination Kennedy Center honoree and a World Series winner.

The selection process continues in 2021 even in the middle of an utterly atypical school year, with finalists from Nevada, North Carolina, Utah, and Washington, D.C., awaiting a final decision from the Council of Chief State School Officers, which has conferred the award since 1952. The winner will be granted access to leadership training, influential policy networks, and a platform to discuss the issues and students they care about for the next 12 months.

But where are these professional exemplars coming from? A new study examines the characteristics of Teachers of the Year over the last three decades, finding that winners disproportionately teach in schools with lower-than-average numbers of low-income kids. Both at the state and national levels, underrepresented teachers include those working with special-needs students, those who teach in elementary and middle schools, and those employed by charter schools.

Lead author Christopher Redding, a professor of educational leadership at the University of Florida, told The 74 in an interview that little previous research focused on the selection process for Teacher of the Year. Given the rarity of education policies and institutions that place educators in leadership roles, he noted, that made it a ripe area for investigation.

“We structured the study to treat the program as something that deserves attention in and of itself,” Redding said. “You want to have a large role for teachers to be able to advocate for the profession, and at least as the program is designed now, it’s really trying to be a vehicle to accomplish that aim. So it seems like we should be asking who is going to have the opportunity to speak on behalf of the teaching profession.”

Redding and co-author Ted Myers used publicly available information to identify over 1,600 state and national Teachers of the Year — each year, the CCSSO picks finalists and an ultimate national winner from the ranks of state Teachers of the Year, who are themselves selected by their districts and state education agencies — between 1988 and 2019. Matching each winner to their respective schools, they used data from a pair of ongoing, nationwide school surveys to compare the Teachers of the Year against the wider population of American educators.

The results show that the winners, and the places they work, are disproportionately drawn from a few categories. Thirty percent of recent National Teachers of the Year have been English instructors, while 23 percent have taught social studies; those percentages are, respectively, three and four times greater than the share of those teachers in the American teaching ranks. No National Teachers of the Year have taught health, foreign languages, or career and technical education, and just one (Tabatha Rosproy, who won last year) has been an early childhood educator.

The authors specifically cite special education staff as being overlooked; while 10 percent of teachers in their nationally representative sample worked with special-needs students, only 3 percent of state-level Teachers of the Year did. Given the pronounced differences in training, credentialing, and work responsibilities between those working in the field versus their peers in general education classrooms, the authors argue, it is reasonable to ask whether their professional concerns will find a voice in the program’s advocacy efforts.

Schools where winners worked tended to be much bigger than other schools in their state, enrolling 415 more students on average. That’s explained somewhat by the fact that Teachers of the Year are generally more likely to come from high schools — some 46 percent of all winners, compared with 20 percent of teachers nationwide. And while charter schools were underrepresented by about three percentage points among those producing Teachers of the Year, magnet schools were slightly overrepresented.

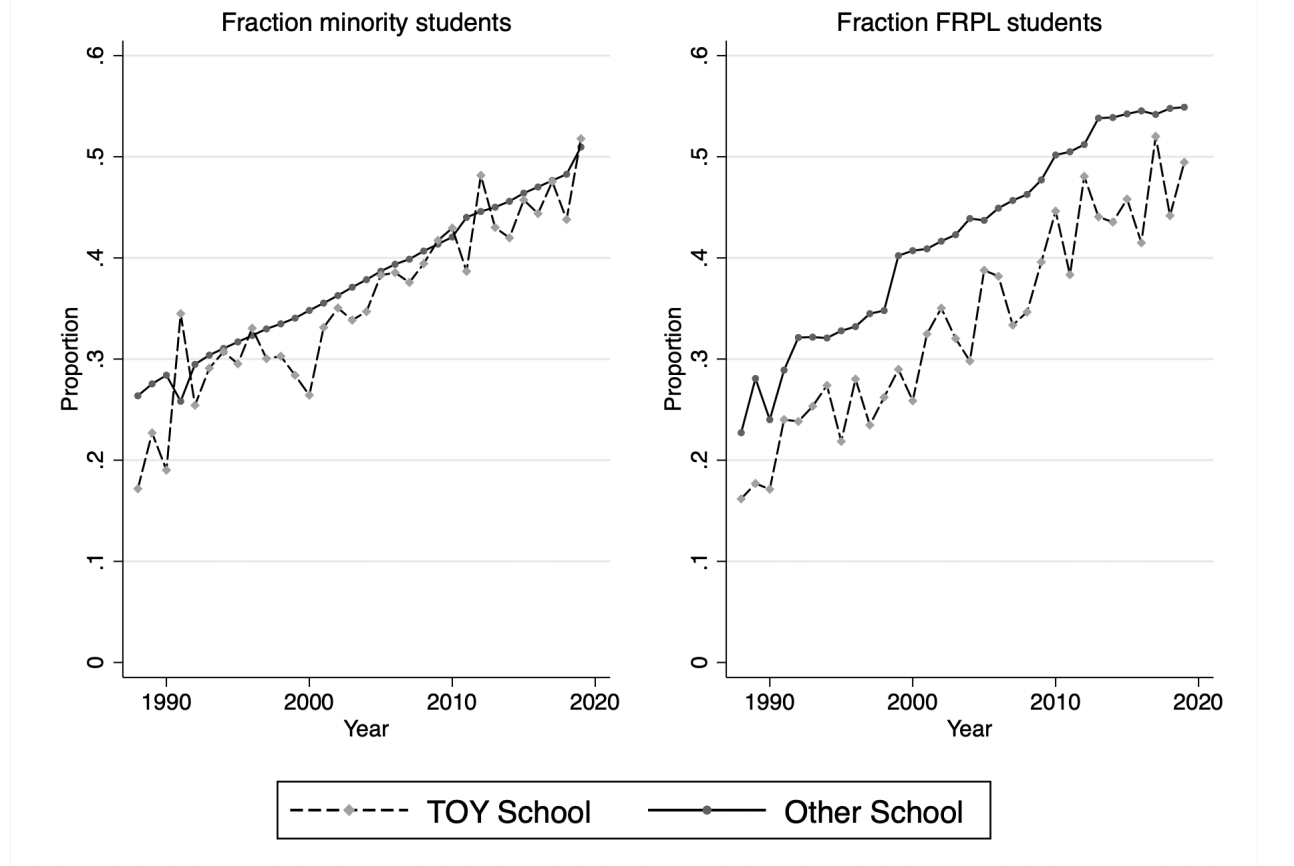

Most strikingly, schools where Teachers of the Year were selected also enrolled 8.4 percent fewer low-income students (those eligible for free and reduced-price lunch) than other schools in their state and award year. In 26 years out of 32 studied, award recipients also worked in schools with smaller shares of minority students than the state average, though the disparity in that instance was narrower (1.7 percentage points).

It’s unclear what factors might explain the trends in selection. The weight of research evidence indicates that top-performing teachers are more likely to work in comparatively affluent schools and districts, while schools that disproportionately enroll more low-income and non-white students tend to hire younger staff with much less classroom experience. Whatever the cause, in Redding’s view, that demographic mismatch raises the question of whether the Teacher of the Year program — one of only a few elevating the voices of school employees, and by far the most prominent — can fully represent the views of most teachers.

“What stands out the most is that it does really seem like teachers from high-poverty schools are less likely to be selected,” he noted. “If that shapes the issues that are being [raised], it underrepresents the ones that might be of most concern to teachers working in high-poverty schools.”

Over the last few years, National Teachers of the Year have increasingly found themselves either willing or reluctant participants in the national conversation around education politics. When Boston charter school teacher Sydney Chaffee received the award in 2017, members of the Massachusetts Teachers Association voted down a motion to offer her congratulations even though she was the state’s first national winner. More recently, 2019 National Teacher of the Year Rodney Robinson harshly criticized Donald Trump after the president declined to attend his award ceremony in person. He has also apologized for tweeting out a joke calling for violence against Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConell.

But the most famous example is that of 2016 winner Jahana Hayes, who used her year of notoriety to begin a political career that has now taken her to Congress.

Sarah Brown Wessling, the interim director of the National Teacher of the Year program (and herself the 2010 National Teacher of the Year), told The 74 via email that the Council of Chief State School Officers was “constantly striving to improve the program and our supports to teachers.”

“CCSSO is proud of state efforts to diversify the selection of State Teachers of the Year, and of the national Selection Committee’s attention to selecting finalists and National Teachers of the Year who can represent teachers and students across the country. Recent National Teachers of the Year have taught in a variety of settings representative of America’s schools and students, from preschoolers in a small town to immigrant and refugee high school students in larger cities.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)