Lost Learning, Lost Students: COVID Slide Not as Steep as Predicted, NWEA Study Finds — But 1 in 4 Kids Was Missing from Fall Exams

Almost a fourth of students who took a leading assessment of academic growth in the fall of 2019 were missing from schools when the baseline exam was given at the start of the current school year. And the missing students are disproportionately children thought to be most at risk of falling behind in school shutdowns, say researchers with the nonprofit assessment group NWEA.

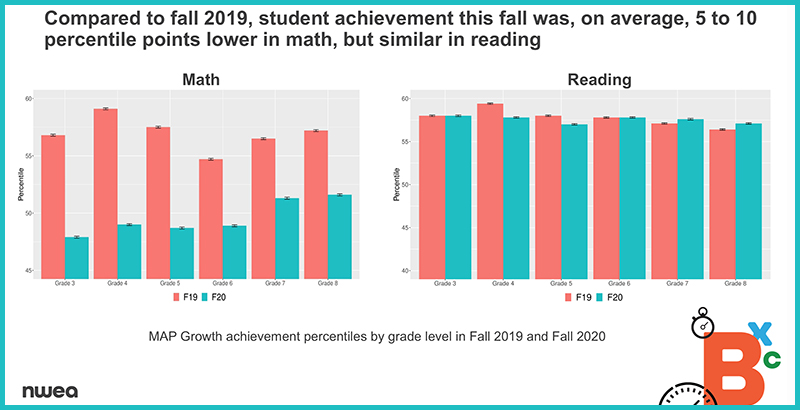

In contrast to dramatic learning losses predicted by NWEA in the spring, the newly released data show steady, if small, improvements since the start of the pandemic in reading and math. But while students in grades 3-8 performed similarly in reading to their same-grade peers in fall of 2020 compared with fall of 2019, they scored 5 to 10 percentile points lower in math.

While the researchers say findings led them to conclude they likely overestimated how much COVID slide students would experience during coronavirus-related school closures, they caution that with such a large number of vulnerable children absent, the research is incomplete. In addition, an unknown number of students took the tests remotely, which may also affect the results.

“Almost one in four are not showing up, and we don’t know why,” said Megan Kuhfeld, a senior research scientist with NWEA. In addition to being disproportionately white, students who did take the fall 2020 tests were more likely to be from affluent schools. Low-income students, children of color and pupils who attend schools with high concentrations of poverty were underrepresented.

With the 2020-21 academic year well underway and the first count day — the date states use to determine schools’ enrollment for funding purposes — behind them, most school systems are starting to calculate the number of students who have gone missing this year. Separate research by Bellwether Education Partners estimated the number of students not in school now at 3 million — more than the school-aged population of Florida.

In April, NWEA’s Collaborative for Student Growth Research Center examined past research on summer slide — the amount of learning lost during the long vacation — and predicted that when they returned this fall, students likely would retain about 70 percent of last year’s gains in reading, compared with a typical school year, and less than 50 percent in math. Historical data, the researchers said, suggested that low-income students, children of color and other underserved populations would experience even more dramatic losses.

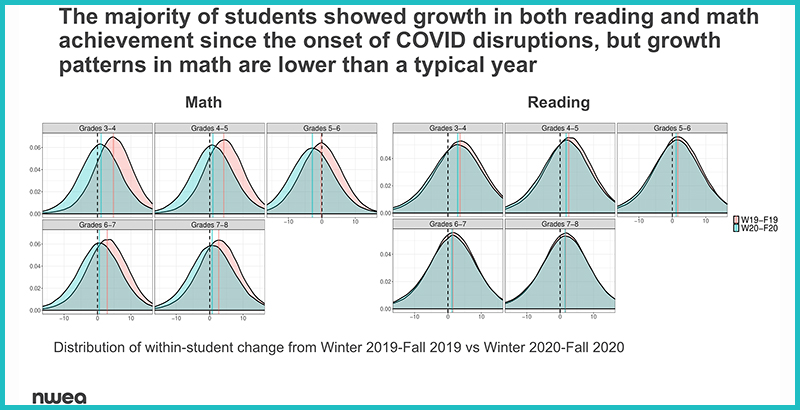

While predictions of student learning gaps were borne out in math in grades 4-6, seventh- and eighth-graders did slightly better than anticipated. Overall, gains in math were smaller than in past fall exams. In all grades, reading scores barely shifted.

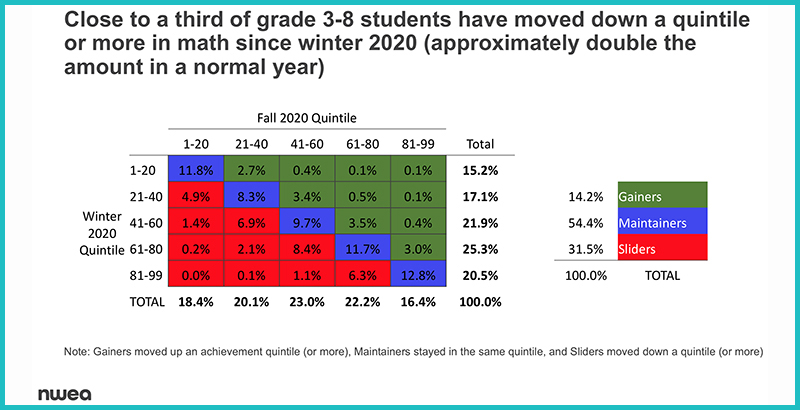

Researchers also looked at whether students were maintaining their relative position in the distribution of test scores, ultimately dividing them into “gainers,” “maintainers” and “sliders.” Slightly more than half maintained their places in both reading and math, though in math, fewer students gained and the number who lost ground nearly doubled in several grades.

NWEA’s findings jibe with research released by other assessment organizations, including Renaissance, a company that creates a similar set of assessments called the Star, and iReady, which is produced by Curriculum Associates.

Kuhfeld and NWEA CEO Chris Minnich said there could be a number of reasons why it was easier for students to stay caught up in reading, ranging from the likelihood that they got better support from their parents than in math to the fact that English language arts instruction revisits the same concepts as students progress, providing opportunities for them to strengthen skills they might have missed. Math, by contrast, is sequential.

In addition to assessing individual students at the start of the year to discern what learning gaps may have widened, experts at a variety of policy organizations have urged schools to use standardized assessments to shine a light on systemwide issues so leaders can better target resources.

Predictions by Bellwether and others about the number of students who are simply absent this year suggest that learning losses not captured by this fall’s assessments will be clustered among students of color, with disabilities, in foster care, learning English, migrant and homeless. As many as one in four children in those demographic groups may not be attending classes anywhere, according to estimates.

“The policy implications are massive,” said Minnich. “When they come back, what’s going to happen? Are they going to be put in the next grade? How do we catch kids up? How do we think about missing learning?”

Disclosure: Andrew Rotherham is co-founder of Bellwether Education Partners and serves on the board of directors of The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)