New Numbers Show More Colleges Using High School Grades, Not Just Standardized Tests, to Determine If Students Require Remedial Coursework

For advocates, change hardly happens fast enough. But over a five-year period, a key barrier to the success of many college students has eroded considerably, opening up the door for thousands of new students to progress through college at higher rates.

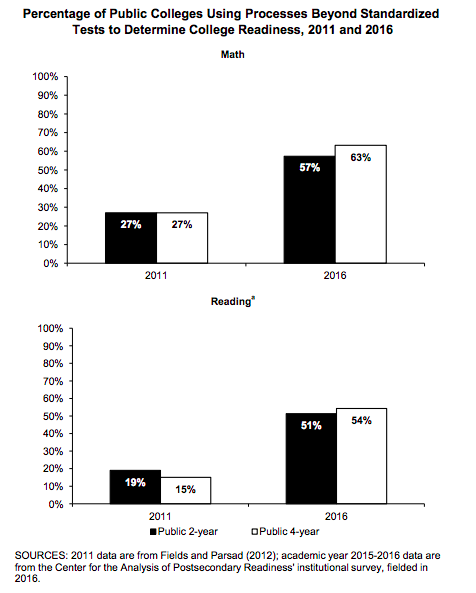

The share of community colleges and four-year public universities that have started to use alternatives to standardized tests to determine whether students are ready for college-level math courses more than doubled between 2011 and 2016, to 57 percent for community colleges and 63 percent for four-year public institutions — up from 27 percent. The November findings are from a representative survey of postsecondary institutions’ approaches to placing students in remedial courses, the first since 2011.

In English, those figures increased to 51 and 54 percent in 2016 for two- and four-year public institutions, respectively, from 19 and 15 percent in 2011.

The survey was in part funded by a federal grant and conducted by the Center for the Analysis of Postsecondary Readiness, a collaboration of MDRC and the Community College Research Center at Columbia University’s Teachers College.

The findings signal a national shift away from relying solely on standardized tests, which a growing chorus of researchers faults for placing more students in remedial courses than is necessary. Other measures, such as high school performance, have shown to be better predictors of whether students will pass a college-level course. As many as 70 percent of college students are told to take remedial courses when they first enter college, which few complete, resulting in dropouts and sunken ambitions.

“You’re seeing that change is happening,” said Elizabeth Zachry Rutschow, the lead author of the report. “If you consider that five years before this survey, almost no one was using anything other than standardized tests, I think that’s a pretty big growth in five years.”

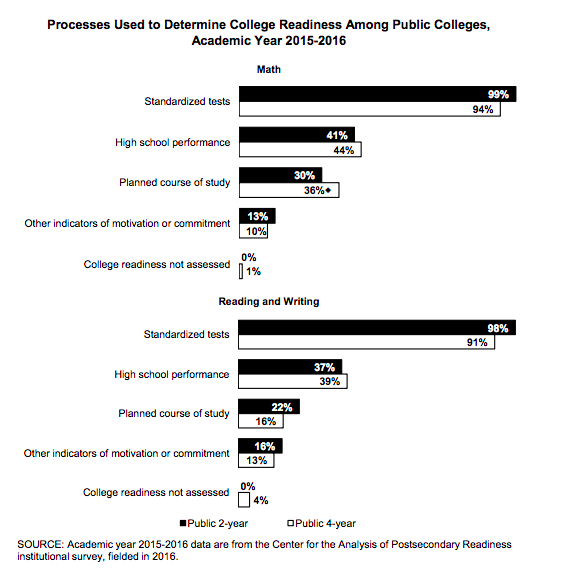

Despite the increased embrace of multiple measures, the survey found that nearly 40 percent of public colleges use only one placement strategy, and 90 percent of those use just standardized tests.

Still, review of high school performance was the second-most popular way of assessing student skills after standardized tests, the report said, “indicating that many colleges may be heeding recent research suggesting that students’ high school grades are a more accurate predictor of their college success.” While more than 90 percent of public institutions used standardized assessments, more than 40 percent relied on high school records.

Placement policy that relies just on placement test results can lead to surprising degrees of misplacement for students in community college. A December research brief published by UC Davis in California showed that students from a large urban school district who enrolled in a nearby community college district between 2009 and 2014 were often placed in remedial math even though they took advanced high school classes. The brief showed that 84 percent of the students who took pre-calculus in high school wound up in remedial math anyway. Of those, nearly a third were placed in pre-algebra or below. Among students who took calculus in high school, just about half were placed in remedial math.

The survey also offers a national snapshot of the strategies colleges are using to teach students determined to need remedial coursework.

Most community colleges and a large share of public universities assigned students to multiple levels of developmental education in 2016, but by then reforms to that model were already noticeable. Those include allowing students to take compressed remedial courses that package several semesters of coursework into one remedial course. Another reform places students deemed in need of remedial support into college-level courses that come with extra tutoring or instruction to catch them up on more basic elements, known as the corequisite model.

The report noted that though “experimentation is widespread, colleges are generally not offering these approaches at scale, with most interventions making up less than half of their overall developmental course offerings.” The report also indicated that more four-year universities had been using developmental education courses in 2016 than in 2000.

The remedial reform landscape has taken off considerably since 2016, however. California State University, the nation’s largest university system, with around 480,000 students, removed remedial courses in time for fall 2018, replacing them with other models, such as the corequisite approach. And a California law implemented this year will shift the community college system from one in which most students were assigned to remedial courses to one in which most aren’t.

A December 2018 analysis of state remedial instruction policies indicated that more than a dozen states had statutes permitting similar reforms to how these courses are taught.

But even when states or college systems recommend or mandate the use of these instructional models, not all institutions may comply, the report showed. In Georgia, “only 64 percent of two-year colleges surveyed use this approach for developmental math instruction and 60 percent for developmental reading and writing,” the report said. By contrast, all universities in Georgia reported using corequisite models. The difference might be in how the two systems were told to embrace the corequisite model — the universities were mandated to do so, while the colleges had more leeway and could adopt methods other than corequisites.

“Clearly colleges are still doing their own thing,” Rutschow said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)