Pandemic Notebook: 13 Students Across America Write About COVID-19, Their Disrupted School Year and the Disorienting New Normal

By Andrew Brownstein | August 2, 2020

A truth of much education journalism is that the people at the center of our stories — the students — are often the most overlooked.

During the pandemic, amid loud debates about COVID-related learning loss, the angst over whether to reopen or not to reopen, and the outrage over the latest Trumpian tweetstorm, it was sometimes easy to miss a quieter story: students grappling with the most disorienting semester of their lives.

To give voice to these experiences, The 74 created “Pandemic Notebook,” our ongoing look at students living and learning during the coronavirus, told in their own words.

The authors range from a third-grader lamenting the “worst summer break ever” to a graduating college senior offering a lighthearted look at how internet memes bring us together. Many of the writers graduated from high school this year, part of a generation bookended by the twin tragedies of 9/11 and COVID-19.

For all of these students, the pandemic was akin to hitting the snooze bar on normal.

Their semester was about much more than adjusting to the frustrating dynamics of remote learning. There was fear — fear for parents working on the front lines in doctors’ offices and restaurants, fear of not being able to stay grounded without in-person contact with mentors and friends. And there was loss, too. Not just graduation ceremonies turned awkwardly virtual, but canceled proms and final seasons of lacrosse and baseball cut short. Some turned on to a new world of Netflix-dominated downtime (does anyone remember Joe Exotic?); others tuned out, rediscovering the joys of reading or learning in the outdoors. Many others found themselves exiled from the virtual world, divided from their peers due to the cold economics of bandwidth.

Part staycation, part home detention

Just 11 days after her high school in Lexington, Kentucky, closed in March, Sadie Bograd laid out the dimensions of the new normal. “I’m conflicted,” she wrote. “Of course, I’m concerned for the health of my family and community. But as self-absorbed as it feels to say it, I’m also worried about not being able to go to prom.” She described life in quarantine as part staycation, part home detention — though like many at the time, she only expected it to last five weeks.

She dug into the ever-growing pile of novels and memoirs on her bedside table and binge-watched the latest seasons of The Good Place and On My Block. “But sometimes,” she acknowledged, “the prospect of an unstructured month incites an overwhelming sense of panic.”

Just 80 miles away in Louisville, Sky Carroll described how the speed with which COVID-19 went from threat to reality caught her and her friends off guard. “We might not finish our game of senior soakers,” wrote the recently graduated senior. “There might not be a prom or class trip. Maybe not even graduation.” She lamented the loss of her final season of lacrosse, a sport she said “helped me grow physically and mentally” and is, “because of the connections I’ve made, the only place I feel I can be my authentic self.”

“I know this all may sound trivial, and it is,” she wrote. “I joke with my friends about ‘the rona’ and laugh about the possibility of a virtual graduation ceremony. But the truth is, I’m scared.”

Fear and isolation

For some students facing the pandemic, the stakes are existential. Rainer Harris, a junior at a New York City Catholic school, worried about losing his “resilient and very stubborn” mom. They’ve always been “very close,” he said. For instance, in the seventh grade, when kids at school called him the n-word, she told Rainer to be proud of it and that their words would only affect him as long he let them.

But in late May, she returned to her job as the practice manager of a pediatrician’s office in Manhattan. The job is high-risk: She engages face-to-face with dozens of sick patients a day, including drawing blood and collecting urine samples. But she is also 55 and Black, putting her at a much higher risk of exposure. “There is cause for me to worry about her safety,” he wrote.

Like many young people across the nation, Emily Bach saw her relationships, routines and responsibilities upended by the virus. For instance, there’s the history teacher she used to meet on Tuesday mornings to check in before class. Most days, they’d make jokes about their school’s poorly scheduled construction or failing sports teams, but on some, the graduated high school senior wrote, “his was the only smile I saw all day.” Attending school, going to club meetings and taking calls all made “the bad days feel more normal.”

For Emily and many of her friends, the pandemic underscored “the crushing impact of isolation on mental health.” A gay sexual assault survivor, Emily found that during the pandemic she became a sounding board for many of her suffering friends. “The comfort and familiarity of my day-to-day life were replaced by the fear and tragedy of watching my friends get sick, both mentally and physically,” she wrote.

Both sides of the digital divide

Is it possible that just four months ago a world existed where many people had never heard of Zoom? In March, Hope Li walked readers through her awkward, glitchy and often hilarious first day of remote learning at Sunny Hills High School in Fullerton, California. “It felt like the first day of school all over again,” she wrote. “The night before, I couldn’t get to sleep.”

It was a day of breathing exercises, barking dogs and weird email messages from school with meant-to-be-inspirational quotes from the likes of Eckhart Tolle. “While some of the kinks have been worked out since that first day,” she wrote, “it’s only the beginning of a long experiment in this brave new world of remote learning.”

Across the country and on the other side of the nation’s digital divide, Brandon Yam struggled for weeks to get an iPad from the nation’s largest school system. His 10-year-old Sony laptop, “glitchy from excessive use,” was the only computer available for a family of 9, wrote the junior at Francis Lewis High School in New York City.

For Yam, this is what distance learning looked like: pinching “the corners of my iPhone 6 screen wide, squinting to see my trigonometry and physics teachers doing practice problems on paper. Even so, my parents still bicker in the background of my Zoom meetings. I double- or triple-check whether my microphone is off to refrain from giving away too much of my home life to teachers and classmates.”

As someone who attends an elite public school and has two working parents, Yam recognizes his privilege amid the struggle. “Still,” he wrote. “it shouldn’t have taken two weeks to get a laptop, and it shouldn’t have been so hard to get simple answers from the district.”

The pros and cons of Netflix

Life in quarantine also introduced new concepts of fun. The pandemic didn’t invent Netflix binging, of course. But in a world where gathering in public was still dangerous, it became nearly ubiquitous. Asher Lehrer-Small, recently graduated from Brown University, seized upon the ways that “the virus puts many of us in the same boat. We’re stuck inside, bored, and unsure of what the future may hold.”

While he previously avoided social media, Asher wrote, digital connectivity now offered an “unexpected solace.” He laughed about the memes spawned from Netflix’s Tiger King and Cardi B’s Instagram transmissions. “Though absolutely no one is glad for the circumstances, our country has never had so much shared content to connect us,” he wrote.

Faced with the same reality, Talia Natterson went in the opposite direction: She shunned television and daily Facetime calls with friends and rediscovered the joys of reading. “I longed for an escape from this new reality of the world around me and my isolation at home,” wrote the sophomore at a Los Angeles private school. “I dreamed of utopias and alternate universes in which coronavirus had never infected people.”

She laughed at Lady Susan’s flirtatious behavior and shuddered at the demise of Dorian Gray. Through these characters and their fictionalized worlds, she imagined a better future. “I am shocked by how unappealing technology has become for me during this ‘corona-cation,’” she wrote.

Siblings, mentors

Some students had very little time for play. With parents working outside the home or lacking fluency in English, these students took on the roles of teachers and mentors to younger siblings. Bridgette Adu-Wadier, a junior from Alexandria, Virginia, is the daughter of émigrés from Ghana. As the first in her family with plans to go to college, she is on an ambitious trajectory, even during the pandemic. Last semester, she took five AP courses, with calculus Zoom meetings outside of regular school hours and essays due Sunday at midnight. But she is also responsible for teaching and caring for her young brothers. “We rarely have 20 minutes of uninterrupted peace,” she wrote.

The new reality left little dividing line between school and family obligations. “Online learning feels like more work than regular school because I am no longer doing assignments in isolation; homework and video calls drop in the middle of real life, which is much more exhausting,” Bridgette wrote. “At school, I’m divorced from my family obligations; at home during a Zoom call, people constantly enter and exit my room, and my brothers inevitably burst in and distract me.”

Safiya Al-Samarrai comes from a family of refugees and recent immigrants from the ancient city of Samarra in Iraq. A first-year college student studying nursing at Middlesex Community College in Lowell, Massachusetts, she also has many responsibilities at home. She helps translate appointments and pays the bills. “And I’m now buying most of the groceries because I’m scared to let my mom and dad leave the house,” she wrote.

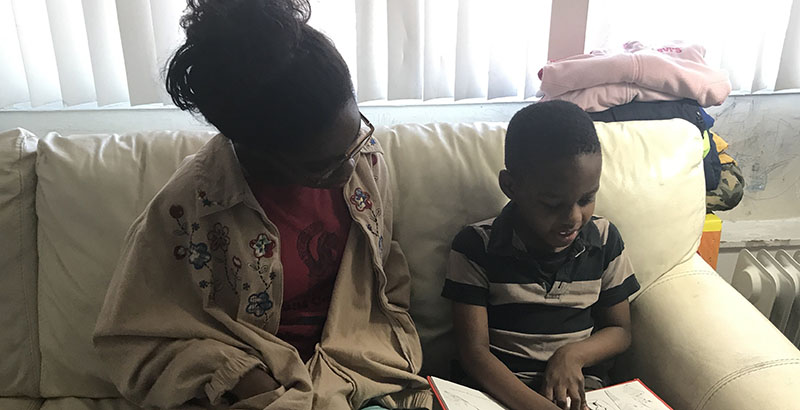

In addition to her parents, she lives with her brothers and 9-year-old autistic nephew, who goes by his nickname Nemo. “The first weeks after our city’s schools closed, Nemo spent every day watching Pokémon,” she wrote. “It upset me that he wasn’t learning. My mom suggested that I try teaching him.”

Loss

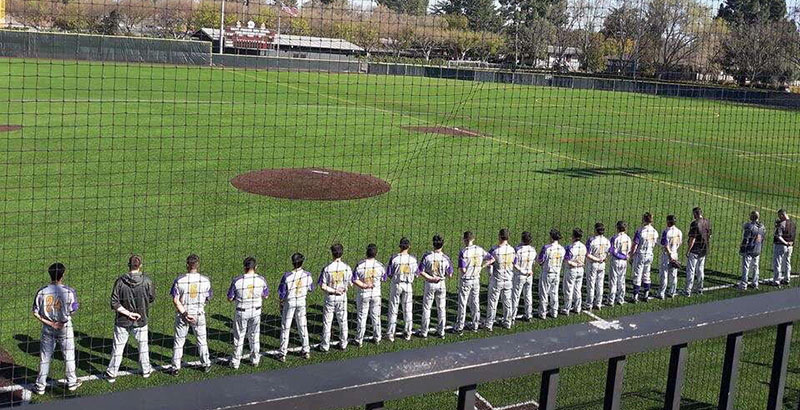

The nation’s first COVID semester was also a time of missed milestones and lost opportunities. Steven Rissotto, a recently graduated high school senior in San Francisco, remembers the night the lights went out on his baseball career. On March 5, Steven was scheduled to relief pitch for his school team. Night games were rare, making them “adored and enjoyed by parents, coaches and players,” he wrote. The mood was festive, highlighted by food and drink. But then the news leaked that the parent of a student at school was diagnosed with the coronavirus, and Steven and his teammates were benched.

It was a tough pill to swallow for Steven, who “fell in love with baseball in third grade and never looked back.” “I love baseball because anything can happen,” he wrote. “The best team could destroy the worst team one day, and it could be the other way around the next. It reminds me about the reality of our current moment.”

As with many students, Sunaya DasGupta Mueller’s academic life from March to June was a litany of sitting in front of her computer for seven hours a day, going in and out of Zoom video classes. For the New Jersey sophomore, the world of largely virtual learning sparked daydreams of a lost childhood. From kindergarten through third grade, she wrote, she attended a nature-based school “where I learned math by knitting, read English books in trees and fed goats in science class. We were discouraged from sitting in classrooms, or having any screen time, even at home. Instead, we painted with abandon, wrote and performed our own plays, and built fairy houses out of acorns in the field.”

During the pandemic, the practice of social distancing helped her realize that active engagement in a learning community is one of the most important aspects of an education. Looking back on her younger years, she wrote that “physical activity, whether doing lab experiments in science, shooting videos for art or solving math problems on a whiteboard, helps make learning real.”

Most summers, Owain Williams, a third-grader in Washington, D.C., would spend time with his family playing in the city’s splash parks and playgrounds, celebrating birthdays and going on trips. “Now, because of the pandemic, all of that is gone,” he wrote.

A month away from summer break, he predicted weeks without fun. “I think that by then, it won’t feel like summer break,” Owain wrote. “It’ll feel like quarantine, because we’ve been home since March.”

“Pandemic Notebook” is an ongoing collection of first-person, student-written articles about what it is like to live through the coronavirus pandemic. Have an idea? Please contact Executive Editor Andrew Brownstein at Andrew@The74million.org.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter