About Half of SC’s 3rd to 8th Graders Read on Grade Level. Math Scores are Worse

Statewide test scores for students in grades 3-8 lagged behind pre-pandemic levels in math.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

COLUMBIA — Fewer than half of South Carolina third- through eighth-grade students can do math as expected for their grade level, according to test scores released Friday.

State education officials hope to improve scores with a new $10 million program to hire math tutors, improve training and pay for resources.

A similar program has helped improve reading scores in recent years, though across the board, test scores are “still not where we need to be, period,” said Sherry East, president of the South Carolina Education Association.

On average, the percentage of students who ended last school year reading on grade level was barely over half, according to the state Department of Education.

Students’ scores on the math portion of the required annual SC READY test remain behind where they were before the COVID-19 pandemic.

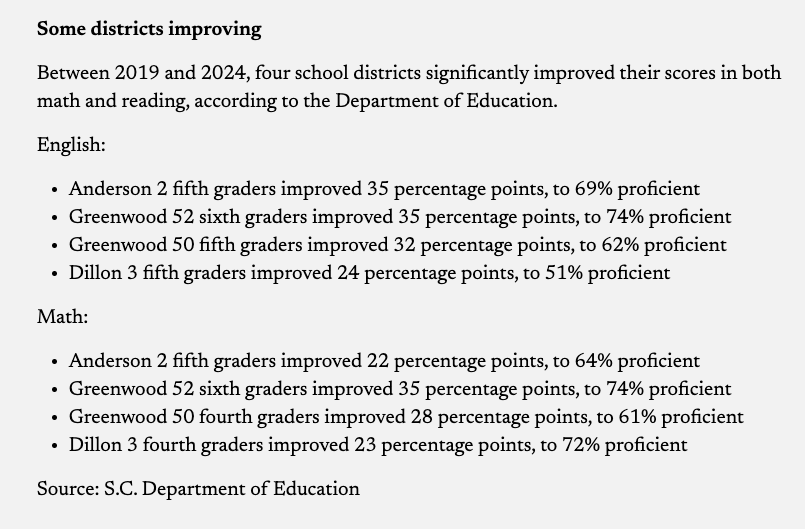

In 2019, 45% of third- through eighth-graders statewide could perform grade-level math, compared to 2024, when 42% of students met expectations. The scores also worsen the older students get. In third grade, about 54% of students were ready to advance to the next grade level, while only 30% of eighth graders met that benchmark.

That leaves high school teachers trying to catch students up to speed, since math skills build each year, said East, a high school science teacher in Rock Hill.

Meanwhile, reading scores have surpassed their pre-pandemic levels, though they remain low. This year, 53% of students met expectations in reading, compared with 45% before the pandemic. State education officials have set a goal that 75% of students test on grade level in both subject areas, though there’s no longer a year for meeting that goal.

Statewide improvement in reading may have come from the Palmetto Literacy Project, East said.

Starting in 2019, a clause in the state budget directed the department to set aside up to $14 million each year to hire reading specialists, train teachers and provide more resources to schools with particularly low scores.

The department hopes to boost math scores using a similar program. With $10 million in this year’s budget, education officials plan to hire math-specific tutors, buy better textbooks and resources, and improve training for teachers at schools where at least one-third of students fall in the lowest category of scores.

“South Carolina’s mathematics scores have consistently lagged and remain stubbornly below even anemic pre-pandemic levels,” the department wrote as the reason for the program when requesting the money.

Whether or not that program proves effective will depend on how the department spends the money and how long it continues, said Patrick Kelly, a lobbyist for the Palmetto State Teachers Association. Math scores are not likely to improve immediately as schools work to implement the program and students learn the skills, he said.

“Turning around math scores isn’t as easy as turning on a light switch,” Kelly said.

While virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic likely played a role in students’ low test scores, it’s not the whole story, East said.

In math, which remains below pre-pandemic numbers, part of the dip could come from residual effects of students not learning fundamentals online. But most students should have had the time to recover, East said.

“We’ve been back at school for two years now,” East said. “I don’t know that we should still see scores where they are.”

Another likely culprit is an ongoing shortage in teachers, she said. The state had more than 1,300 open positions for teachers, counselors, librarians and other education professionals in February, according to a report from the Center for Educator Recruitment, Retention and Advancement. That was down from a record high of more than 1,600 vacant positions when the school year started.

As teachers take on bigger classes, students are more likely to miss out on one-on-one instruction, said Kelly, who’s also a high school teacher in Richland Two. Other classrooms may rely on a long-term substitute who doesn’t always know the subject material or how to teach it, he said.

“You have large pockets of students in this state that are either in overcrowded math classes or in classrooms without a certified teacher at all,” Kelly said.

Poorer districts are more likely to feel those effects. Fewer resources often means fewer certified teachers, fewer options for struggling students and larger class sizes, leading to lower test scores, East said.

Some districts react to low test scores by requiring more tests, but that should not be the case, Kelly said.

Testing often takes away time during which students could actually be learning skills, and the scores are not always an accurate reflection of how well a student is performing. Instead, schools should focus on proven ways to best teach the material, he said.

“The goal is not to reach an abstract number,” Kelly said. “The goal is to help each student reach their potential.”

Students in Fort Mill (York 4) posted the best scores in the state.

Across fourth through eighth grades, at least 75% of the district’s students could read on grade level, and 76% of third-graders met math expectations. The fast-growing school district just south of Charlotte also posts the state’s lowest poverty rate, with 21% of students living in poverty compared to a statewide average of 62%, according to state agency data.

SC Daily Gazette is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. SC Daily Gazette maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Seanna Adcox for questions: info@scdailygazette.com. Follow SC Daily Gazette on Facebook and X.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter